Nature and Scope

The Selection of Material for Eighteenth Century Journals

The journals collected together in Eighteenth Century Journals I are illustrative of the wide range of print options available to the periodical reader of the age, and the variety of subjects covered by such works. From the ephemeral to the long-running; from the political controversies of the day to the latest gossip from London society; from the works of Coleridge in his Watchman to the anonymous offering of a never-to-be known poet: these journals provide an invaluable insight into the eighteenth-century world. The views represented within these texts are often in opposition to those of the government or other established bodies; indeed, they are often in opposition with one another. They are not homogenous, and they are, therefore, a testament to the vibrancy and variety of their time.

These are the times that try men’s souls. The Summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the thanks of men and women. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.

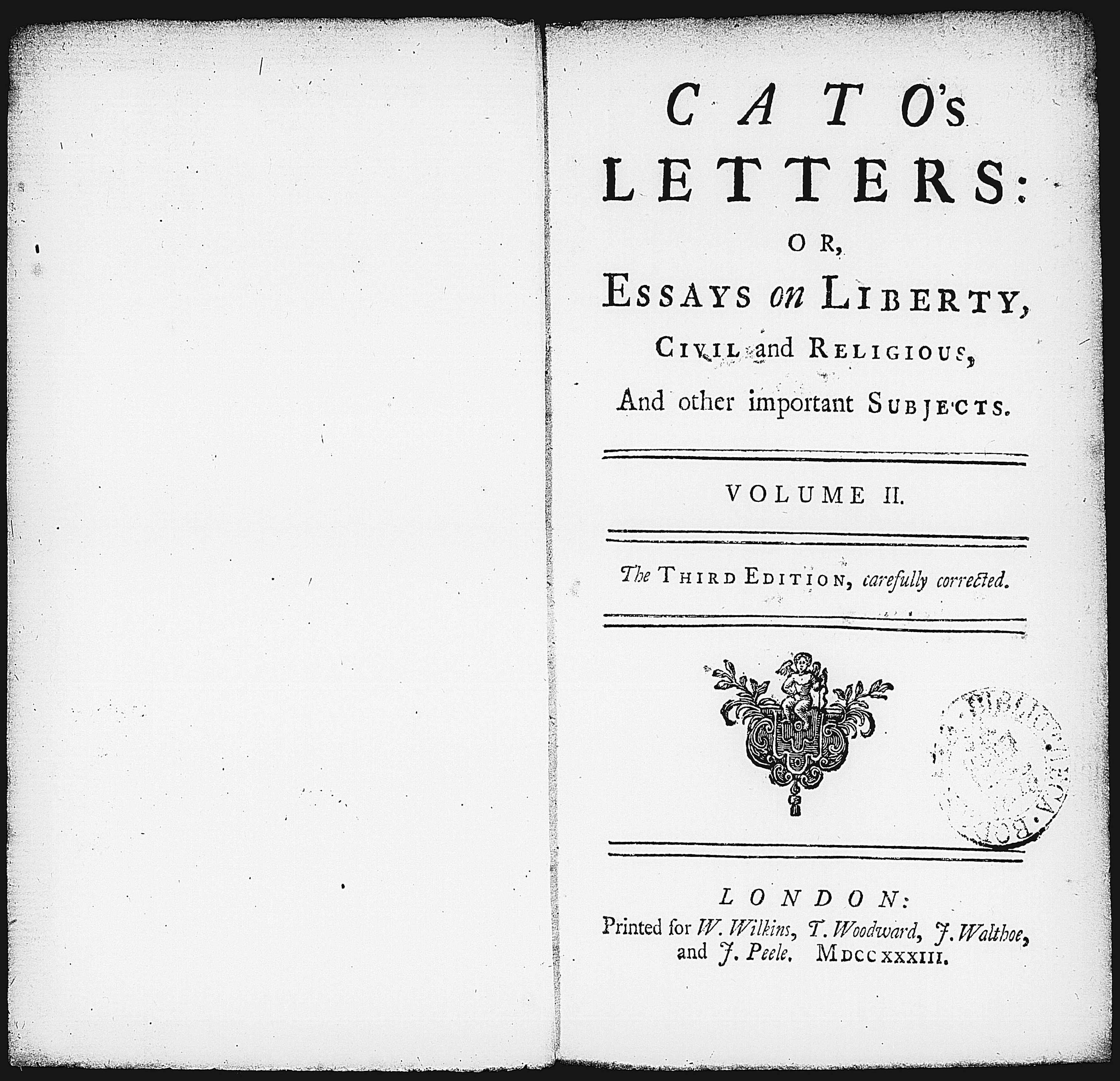

Other political controversies prompted opposing sides to iterate their arguments in print. The Plebeian and the Old Whig see Sir Richard Steele and Joseph Addison (respectively) pitted against each other in a political quarrel. In the Plebeian Steele attacked the Earl of Sunderland’s proposed Peerage Bill, which had divided the Whig party; the Old Whig offers Addison’s counter-attack on Steele, whom he termed ‘Little Dicky, whose trade it was to write pamphlets.’ The Director is written in advocacy of the South Sea scheme while Cato’s Letters (1720-1723) was written initially as a call for public justice on the managers of the South Sea Bubble and printed in the London Journal. However, Cato’s Letters was continued over three years to cover a wide range of subjects, always advocating freedom of speech and freedom from tyranny and advancing the concepts developed by John Locke. These letters proved highly popular and influential, and were reprinted as a journal in their own right many times. A generation later they were an inspiration to the American Colonists (half of the private libraries in America were said to hold a copy). This is both a testament to the power of the period’s press, and to the ongoing value of these journals as a means for contemporary understanding of eighteenth-century political and cultural life.

Other political controversies prompted opposing sides to iterate their arguments in print. The Plebeian and the Old Whig see Sir Richard Steele and Joseph Addison (respectively) pitted against each other in a political quarrel. In the Plebeian Steele attacked the Earl of Sunderland’s proposed Peerage Bill, which had divided the Whig party; the Old Whig offers Addison’s counter-attack on Steele, whom he termed ‘Little Dicky, whose trade it was to write pamphlets.’ The Director is written in advocacy of the South Sea scheme while Cato’s Letters (1720-1723) was written initially as a call for public justice on the managers of the South Sea Bubble and printed in the London Journal. However, Cato’s Letters was continued over three years to cover a wide range of subjects, always advocating freedom of speech and freedom from tyranny and advancing the concepts developed by John Locke. These letters proved highly popular and influential, and were reprinted as a journal in their own right many times. A generation later they were an inspiration to the American Colonists (half of the private libraries in America were said to hold a copy). This is both a testament to the power of the period’s press, and to the ongoing value of these journals as a means for contemporary understanding of eighteenth-century political and cultural life.

List of Module I Journals by Subject Area (links to first volume)

Literary Journals

(See also Theatrical Journals)

The Adventurer 1753

The Attic Miscellany 1789

The Bee Reviv'd 1750

Cato's Letters 1720-23

The Centinel 1757

The Critick 1718

The Devil 1786-87

The Eaton Chronicle 1788

The Entertainer 1718

The Flapper 1796-97

The Fool 1746-47

The Free-Thinker 1718-21

The Genius 1762

Genius of Kent 1792-93

The Gentleman 1775

Hog's Wash 1793-95

The Humourist 1720

The Kapelion 1750-51

The London Mercury 1780

The Microcosm 1786-87

The Phoenix 1797

The Rhapsodist 1757

The Speculator 1790

Terrae Filius 1763

The Tribune 1729

Variety 1788

The Watchman 1796

The World 1753-56

Moral and Satirical Journals

The Attic Miscellany 1789

The Busy Body 1787

The Country Gentleman 1726

The Covent-Garden Journal 1752

The Devil 1755

The Doctor 1718

The Eaton Chronicle 1788

The Flapper 1796-97

The Fool 1746-47

The Humourist 1720

The New Spectator 1784-86

The Quiz 1796-97

The Royal Female Magazine 1760

The Spy at Oxford & Cambridge 1744

The Trifler 1795-96

The World 1753-56

Political Journals

The American Crisis 1776-80

The Anti-Union 1798-9

The Budget 1764

Cato's Letters 1720-23

The Controller 1714

The Country Gentleman 1726

The Covent-Garden Journal 1752

The Crisis 1775-76

The Crisis 1792-93

The Daily Benefactor 1715

The Director 1720-21

The English Freeholder 1791

The Entertainer 1754

The Fall of Britain 1776-1777

The Fish-Pool 1718

The Fool 1746-47

The Free Briton 1729-35

The Free-Thinker 1718-21

Genius of Kent 1792-93

Hog's Wash 1793-95

A Letter from J-n W-s 1764

The London Mercury 1780

The Microcosm 1786-87

The National Journal 1746

The New Spectator 1784-86

The North Briton 1764

The Old Whig 1719

Pig's Meat 1794

The Plebeian 1719

The Political Herald & Review 1785

The Protestant Packet 1780-81

The Scots Spy 1776

The Spinster 1719

Town Talk 1715

The Tribune 1729

The Tribune 1795-96

The Wallet 1764

Wilkes & Liberty 1764

The World 1753-56

Religious Journals

The Comedian 1732

The Christian's Amusement 1740-41

The Daily Benefactor 1715

The Entertainer 1754

The Free-Thinker 1718-21

Genius of Kent 1792-93

Hog's Wash 1793-95

The Protestant Packet 1780-81

The Weekly History 1741-42

Theatrical Journals

The Adventurer 1753

The Anti-Theatre 1720

The Attic Miscellany 1789

The Centinel 1757

The Comedian 1732

The Covent Garden Chronicle 1768

The Crisis 1792-93

The Devil 1786-87

The Genius 1762

The Gentleman 1775

The Kapelion 1750-51

The New Spectator 1784-86

The Prompter 1789

The Rhapsodist 1757

The Speculator 1790

The Theatre 1720

The Theatrical Monitor 1767

The World 1753-56

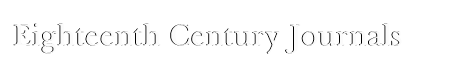

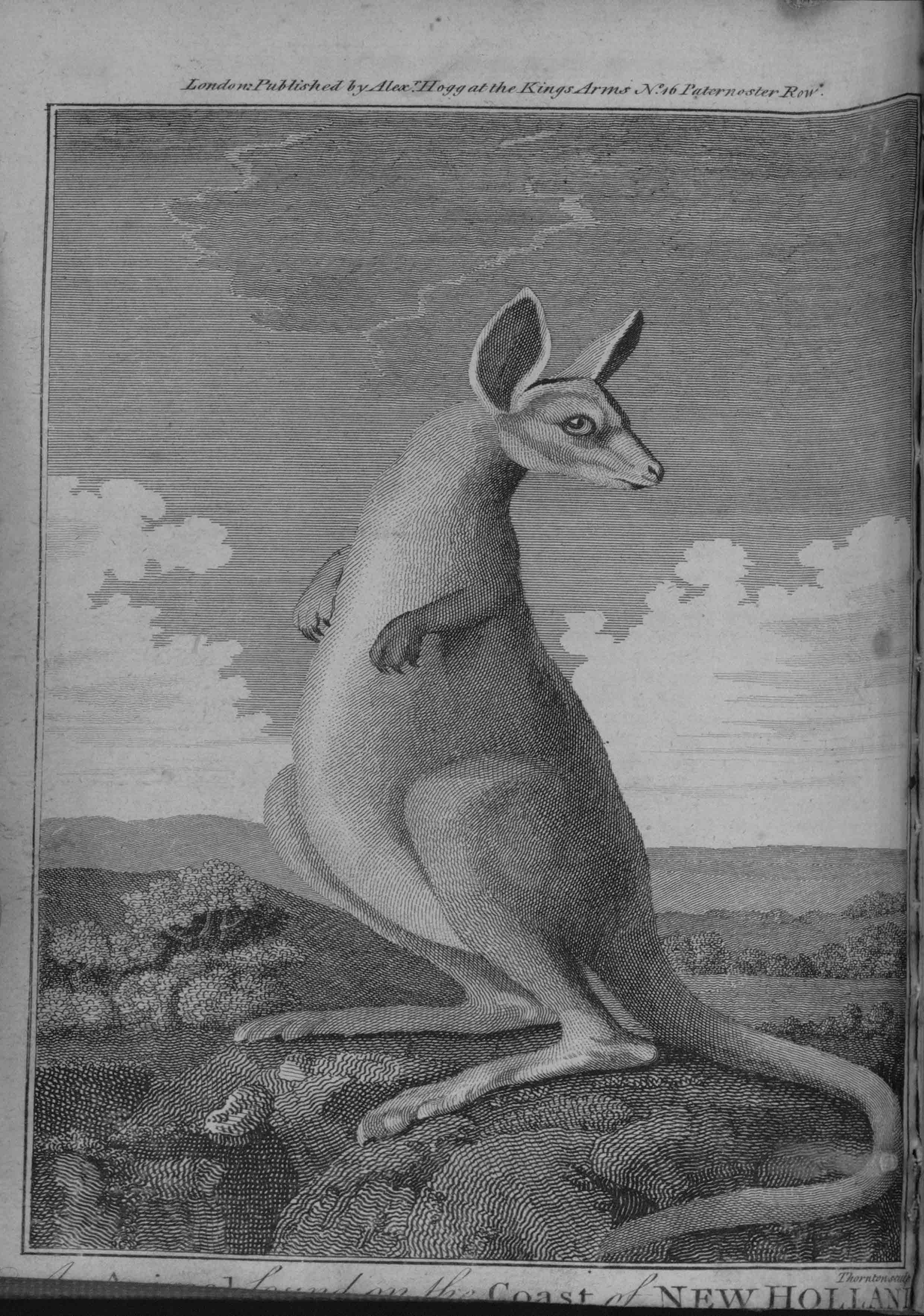

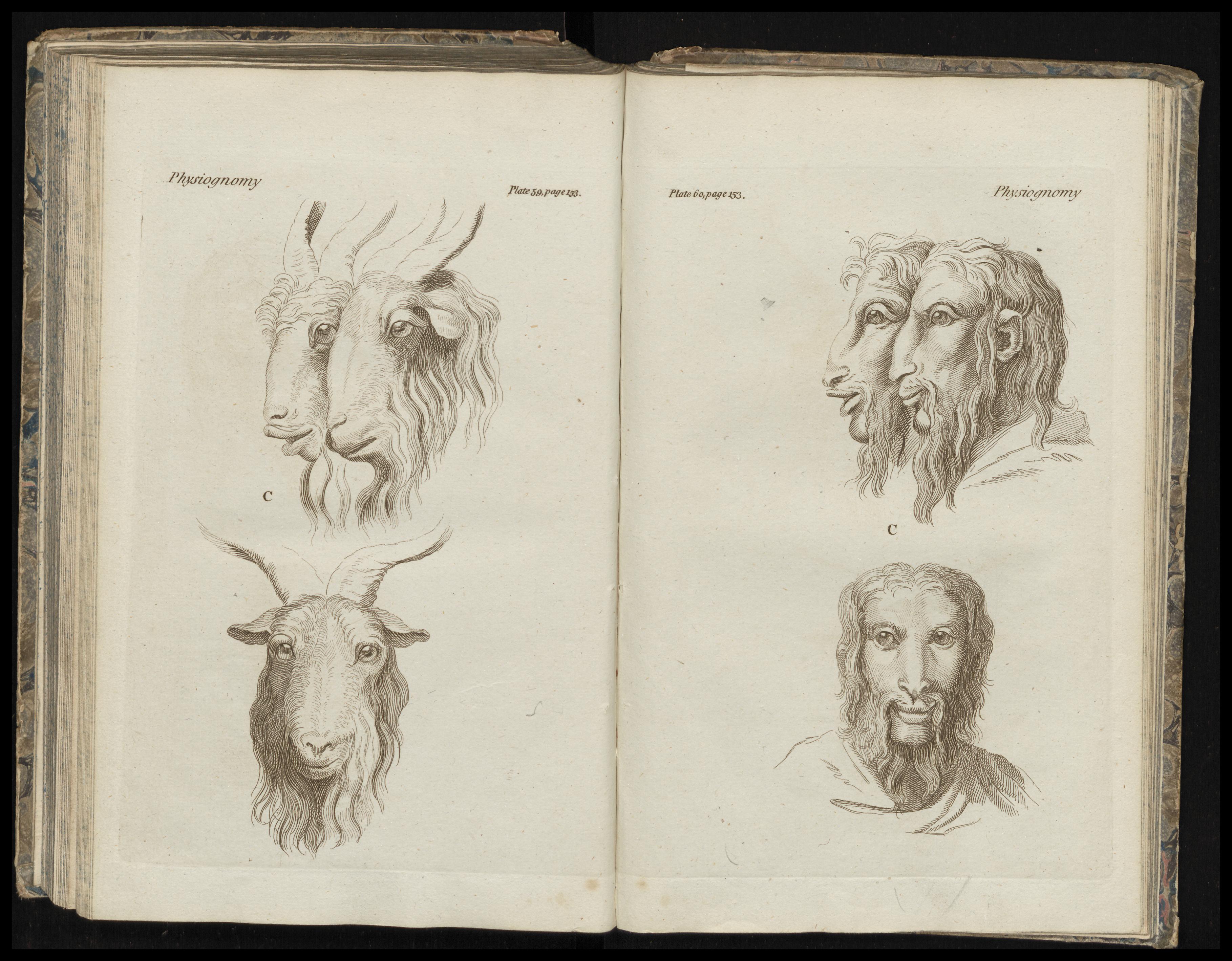

Eighteenth Century Journals II provides a wide-ranging view of topical issues that concerned readers of the period. In the eighteenth century, as today, the content of newspapers was dictated by the editor’s sense of what was desired by the general readership. This desire can be summed up in a single word: variety. Themes covered by the periodicals featured in this digital collection are highly diverse, including literature, the theatre; fashion; politics, revolution; agriculture; social issues and society life. Moreover, such range of topics is often discussed within the pages of a single volume, leaping from discussions of the latest ladies’ fashions, to the study of natural philosophy, to gardening methods, within a matter of pages. The sheer breadth of subject matter is astonishing. This essay will attempt to provide the user with a flavour of such subjects and how they were approached by eighteenth-century publishers. It concludes with a list of some relevant journals which users may find a helpful starting-point in their research on specific subject disciplines.

Eighteenth Century Journals II provides a wide-ranging view of topical issues that concerned readers of the period. In the eighteenth century, as today, the content of newspapers was dictated by the editor’s sense of what was desired by the general readership. This desire can be summed up in a single word: variety. Themes covered by the periodicals featured in this digital collection are highly diverse, including literature, the theatre; fashion; politics, revolution; agriculture; social issues and society life. Moreover, such range of topics is often discussed within the pages of a single volume, leaping from discussions of the latest ladies’ fashions, to the study of natural philosophy, to gardening methods, within a matter of pages. The sheer breadth of subject matter is astonishing. This essay will attempt to provide the user with a flavour of such subjects and how they were approached by eighteenth-century publishers. It concludes with a list of some relevant journals which users may find a helpful starting-point in their research on specific subject disciplines.This collection also offers us a rare glimpse of the more ephemeral aspects of the period. Almanacs such as Culpepper Reviv’d, and Rose’s Almanack for the Year from the Nativity…1712 provide catalogues of the year’s fairs and notable dates, while Merlinus Redivivus specialises in an astrological interpretation of the calendar. The Oeconomist advises gentlemen on the smooth regulation of household affairs and agriculture management, offering information on leases, tithes and “making Ox-head soup”. From accounts of “Country Beauties Spoilt by London Fashions” (Universal Museum) to “Curious Remarks on the Customary Time of Eating” (New London Magazine), these journals vivify the daily minutiae of 18th century life.

List of Module II Journals by Subject Area (links to first volume)

Mercurius Politicus

Old Common Sense; Or, the Englishman’s Journal

The Champion

The Con-Test

The Free-Holder

The Grumbler

The Monitor

The Political Magazine and Parliamentary, Naval, Military and Literary Journal

The Political Register

Weekly Remarks and Political Reflections

The Vocal Magazine

The New London Magazine

The British Magazine

The Universal Museum

B Berington’s Evening Post

The British Merchant; Or, Commerce Preserv’d

B Berington’s Evening Post

Old Common Sense; Or, the Englishman’s Journal

Parker’s Penny Post

Pax, Pax, Pax; Or, A Pacifick Post-Boy

St. James’ Evening Post

St. James’ Post

The Dublin Evening Post

The Edinburgh Gazette

The Flying Post

The London Journal

The London Packet; Or, New Lloyd’s Evening Post

The Morning Advertiser

The Morning Post and Fashionable World

The Northampton Mercury

The Original Weekly Journal

The Plain Dealer

The Post Angel

The Whitehall Evening Post

The York Chronicle

The York Courant

The Bee; Or Literary Weekly Intelligencer

The British Magazine

The New London Magazine

A Pacquet from Parnassus

The Lay-Monk

The Medley

The Museum; Or, the Literary and Historical Register

The Oeconomist

The Post Angel

The Royal Magazine; Or, Quarterly Bee

The Universal Museum

The British Magazine

Censura Temporum

A Pacquet from Parnassus

The Bee; Or Literary Weekly Intelligencer

The Muses Mercury

The Museum; Or, the Literary and Historical Register

The New London Magazine

The History of the Works of the Learned

The Political Magazine and Parliamentary, Naval, Military and Literary Journal

The Present State of the Republick of Letters

The Universal Museum

Eighteenth Century Journals III, like previous sections, celebrates the variety and diversity of eighteenth century publishing with a range of newspapers and magazines covering all sorts of subjects. This section, however, focuses largely on material published outside of London, including newspapers from across the British Empire, Ireland, Scotland and provincial England. This essay outlines the context of some of the colonial newspapers to help users begin their research. A subject list and a brief guide to some of the other highlights of the collection are also included.

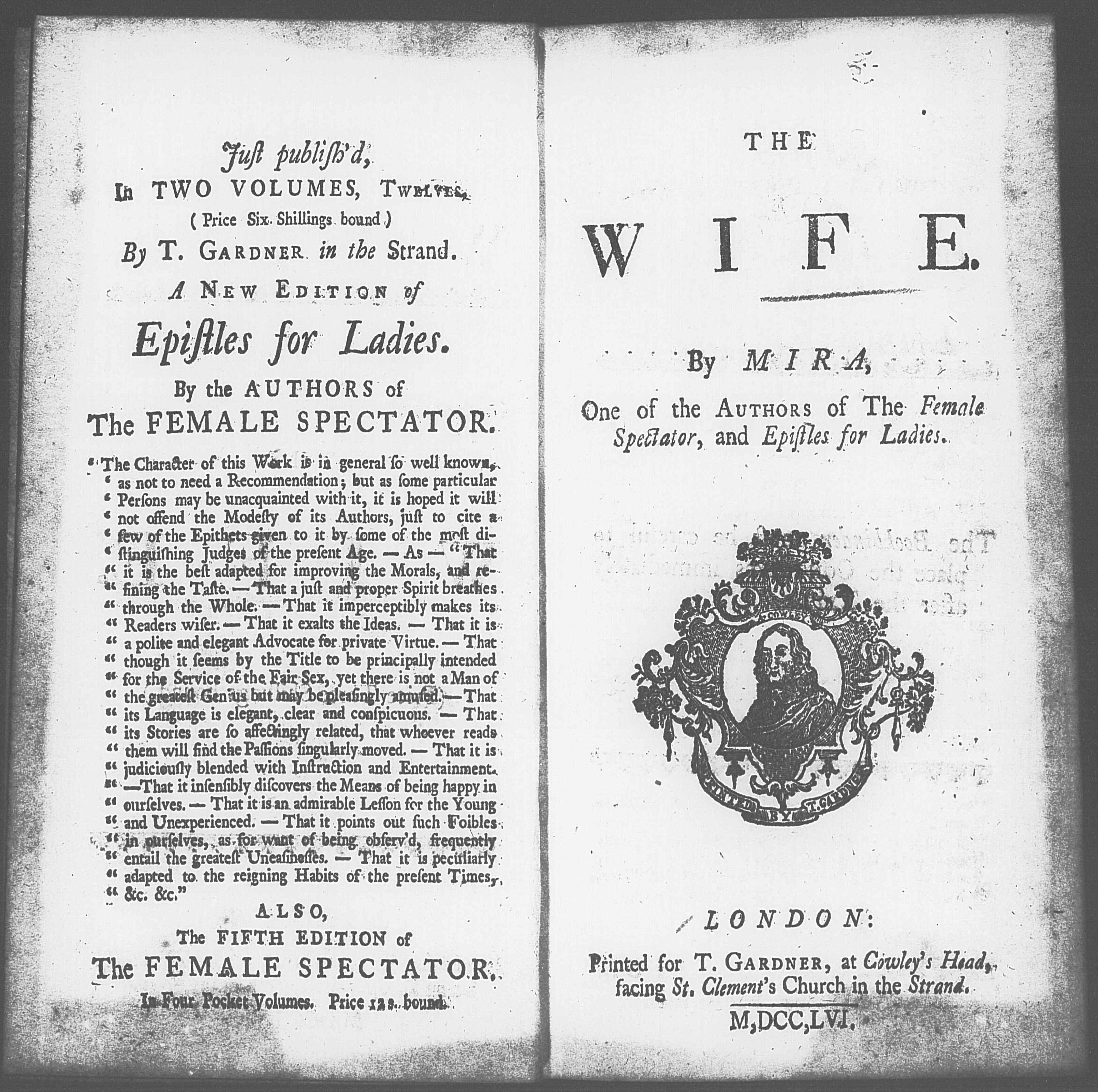

There are four titles from Kingston, Jamaica (the Jamaica Mercury and Kingston Weekly Advertiser, later the Royal Gazette; the Daily Advertiser; and the Kingston Journal), reflecting the importance of Caribbean settlements to the British Empire in the eighteenth century. Jamaica, siezed from Spain in 1655, benefited greatly from the sugar boom in the late 1700s which ensured that it generated one of the highest incomes of any British colony. As with all the colonial newspapers included in this collection, the advertisements featured in these Jamaican titles offer fascinating insights into daily life in Britain’s colonies. Central to Jamaica’s plantation system was slave labour, and the importance of slaves to the white planters is evidenced by the high number of advertisements for runaway slaves in local periodicals.

It occurred to Hicky that great benefit might arise from setting on foot a public newspaper, nothing of that kind ever having appeared…. As a novelty every person read it, and was delighted. Possessing a fund of low wit, his paper abounded with proof of that talent. He had also a happy knack at applying appropriate nicknames and relating satirical anecdotes.

I am shocked to observe the constant endeavours of malecontents to effect a total subversion of peace and harmony amongst us. We are now at war with five or six different Powers, each of which possesses a tract of Country many degrees larger than our own, and is infinitely more populous; under these circumstances, unanimity alone can enable us to resist the torrent of destruction that has long threatened to burst on our heads. That there are in Bengal, some who are ill-affected to the true interests of their country, is, I think, evident from the many inflammatory letters and Paragraphs that have appeared in the Bengal Gazette, which seem to breathe a strong spirit of discontent. (India Gazette, or, Calcutta Public Advertiser, Volume 1, Issue 12)

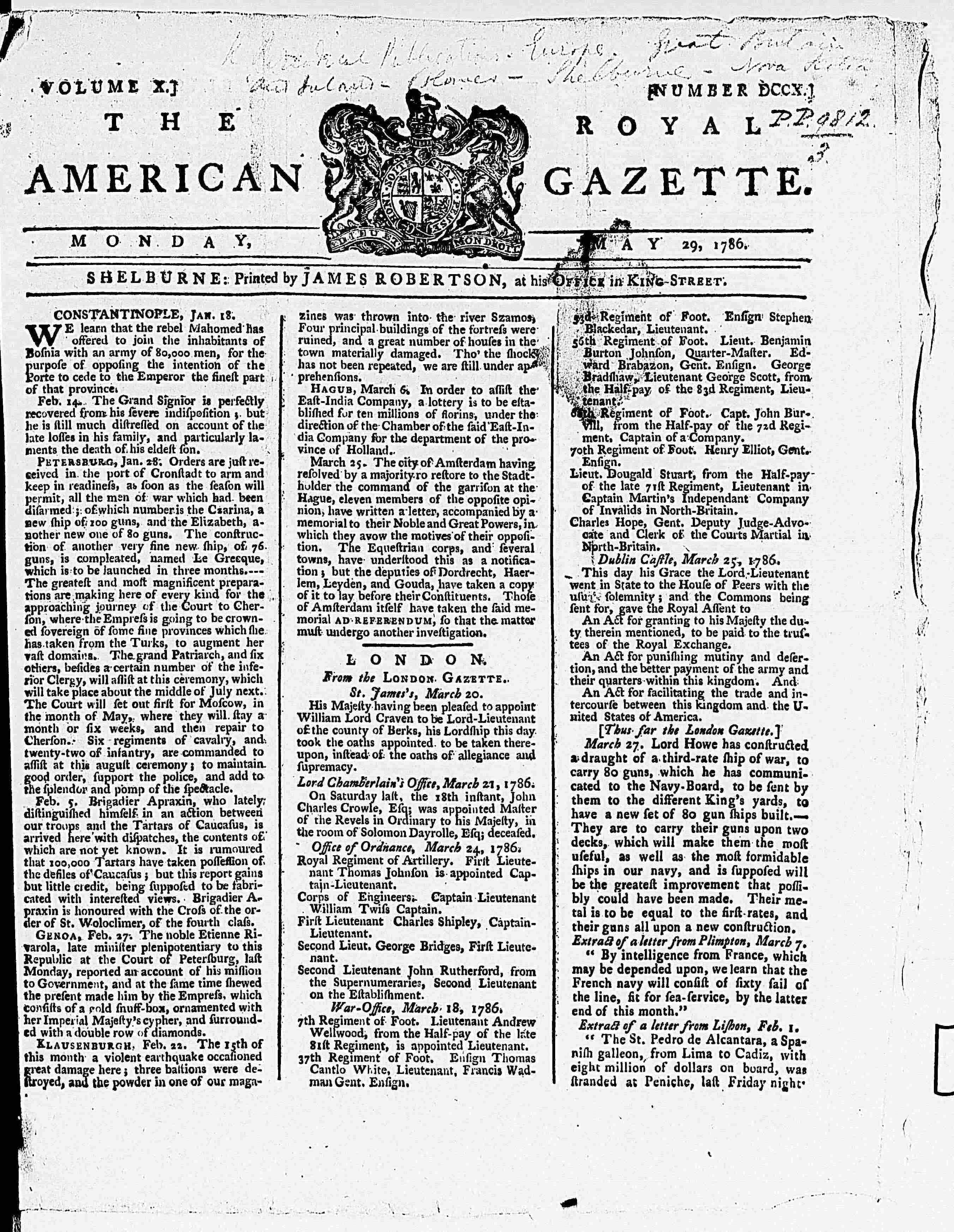

Printed newspapers in Canada started life in 1752 in the British colony of Nova Scotia with the publication of the single-sheet newsletter The Halifax Gazette – in 1766 this became the four-page Nova Scotia Gazette, printed here. The newspaper continues to be printed in Halifax today under the name The Royal Gazette. The emergence of a dominant Anglo-protestant culture in Nova Scotia between the 1750s and 1780s, beginning with the Great Explusion of Acadians and continuing with the arrival of United Empire Loyalists after American Independence, is charted in the rise of English-language newpapers in Nova Scotia during this period. For example, the Royal American Gazette was first published in New York in 1777 by the Robertson brothers, but was moved to Shelburne, Nova Scotia in 1783, due to the brothers’ loyalist views, and continued publication there.

Printed newspapers in Canada started life in 1752 in the British colony of Nova Scotia with the publication of the single-sheet newsletter The Halifax Gazette – in 1766 this became the four-page Nova Scotia Gazette, printed here. The newspaper continues to be printed in Halifax today under the name The Royal Gazette. The emergence of a dominant Anglo-protestant culture in Nova Scotia between the 1750s and 1780s, beginning with the Great Explusion of Acadians and continuing with the arrival of United Empire Loyalists after American Independence, is charted in the rise of English-language newpapers in Nova Scotia during this period. For example, the Royal American Gazette was first published in New York in 1777 by the Robertson brothers, but was moved to Shelburne, Nova Scotia in 1783, due to the brothers’ loyalist views, and continued publication there.List of Module III Journals by Subject Area (links to first available volume)

India

Hircarrah

Asiatic Mirror, and Commercial Advertiser

Bengal Lottery

Calcutta Chronicle; and General Advertiser

Calcutta Morning Post Extraordinary

Calcutta Friday Morning Post and General Advertiser

Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, or Calcutta General Advertiser

India Gazette, or Calcutta Public Advertiser

World

Madras Gazette

Bombay Courier

Bombay Gazette

Calcutta Gazette; or Oriental Advertiser

Ireland

Sligo Journal and Weekly Advertiser

Westmeath Journal

Limerick Journal

Munster Journal

Weekly Amusement; or, Universal Magazine

Drogheda Journal; or, Meath and Louth Advertiser

Clare Journal

Hibernian Journal: or, Chronicle of liberty

Strabane journal. Or the general advertiser

London-derry journal. And, Donegal and Tyrone advertiser

Dublin Evening Post

Freemason’s journal: or, Pasley’s universal intelligencer

Whigg-monitor

Drogheda Journal

Strabane Journal

Cork Journal

Ferrar’s Limerick Chronicle

Mirror

Cork herald: or, Munster advertiser

Weekly amusement; or, Universal magazine

Dublin Evening post

Patriot

Cork Courier

Press

Belfast news-letter

Caribbean

Daily Advertiser

Bermuda Gazette and Weekly Advertiser

Kingston Journal

Jamaica Mercury and Kingston Weekly Advertiser

Royal Gazette

Canada

Royal American Gazette

Nova-Scotia Gazette and Weekly Chronicle

Nova-Scotia Packet and General Advertiser

Nova-Scotia Gazette

Scottish and Provincial English

University magazine (Cambridge)

Kentish chronicle (Canterbury)

Billinge’s Liverpool advertiser (Liverpool)

Lounger (Edinburgh)

Ipswich Journal; or, the Weekly Mercury

Farmer’s magazine (Edinburgh)

Magazines and Miscellanies

Spirit of the Public Journals

British Military Library; or, Journal

Oriental repertory…in four numbers

Rehearsal rehears’d, in a dialogue between Bayes and Johnson

Monthly London Journal: containing, the most material occurences...

Britannic magazine; or Entertaining repository of heroic adventures

Weekly Journal with fresh advices foreign and domestick

Heraclitus ridens (London)

Scourge in vindication of the Church of England

Herald, or patriot proclaimer

Weekly pacquet of advice from Rome restored: or, The history of Popery continued

Tribune (London)

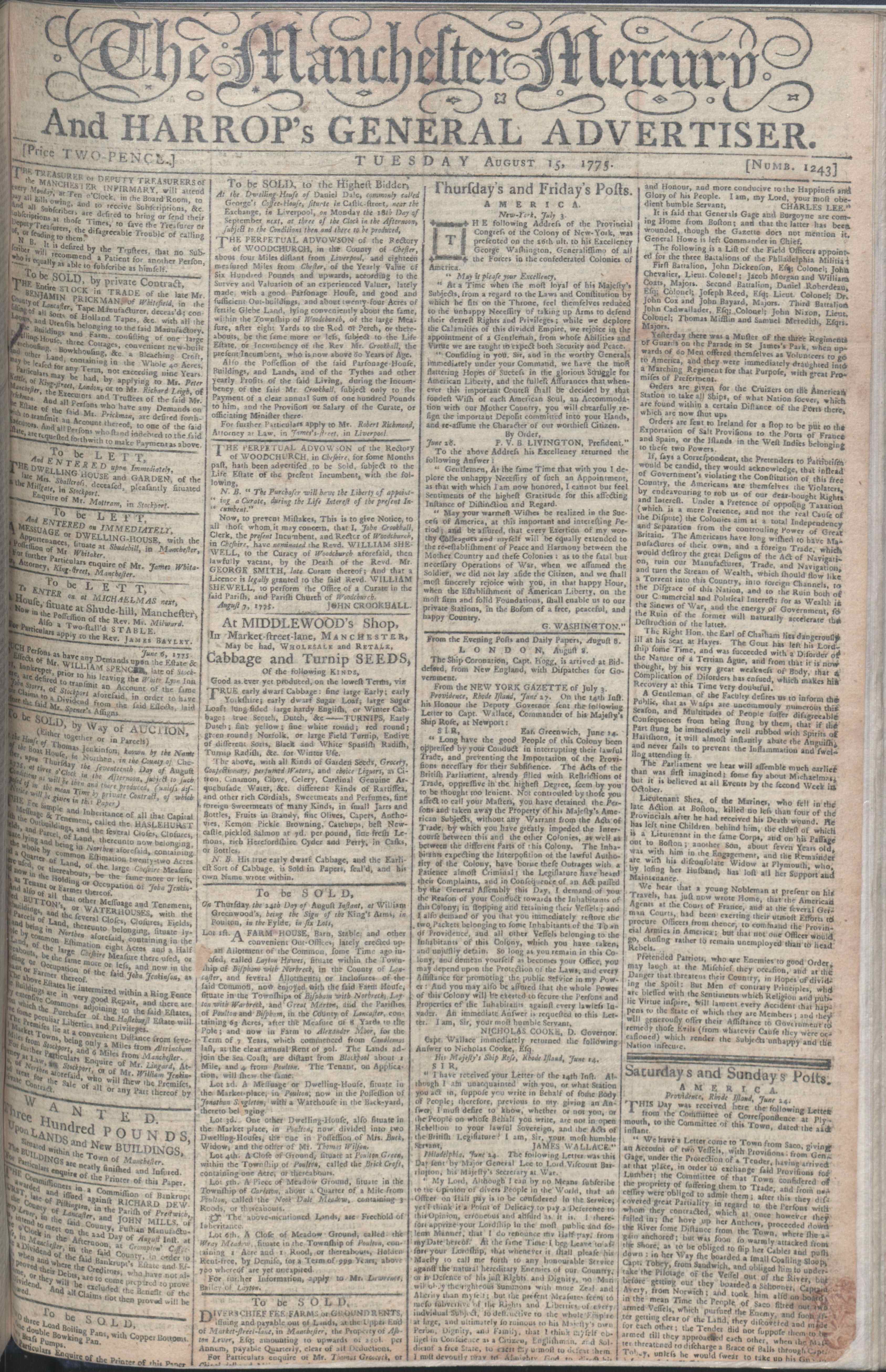

In the eighteenth century, London’s economic and political influence receded with the rising importance of towns and cities like Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, Bristol and Glasgow. In order to explore this subtle shifting of power away from London and to follow on from Eighteenth Century Journals III, which also focuses on material published outside of London, Eighteenth Century Journals IV contains key material published in Manchester during this time of rapid industrial change and political turmoil. This essay aims to provide a contextual background to some of the newspapers included in this section. Selected highlights from the collection and a subject list are also provided.

Early eighteenth century newspapers were predominantly published in and circulated around London and were only accessible to a minority who could afford them. But, as the century progressed, a number of developments led to a dramatic increase in newspaper circulation and readership: better transport networks led to a growth in the number of provincial papers, a rising middle class benefiting from industrial progress could increasingly afford to buy newspapers and the rise in popularity of coffee houses meant that more of the lower classes had access to free newspapers. By the end of the eighteenth century, Great Britain had over three hundred different newspapers. While many of these were still published in London or contained details of London affairs, such as Bell’s Weekly Messenger, The British Critic and Memoirs of Literature, which are just a few of the London titles included in Eighteenth Century Journals IV, many newspapers covered local news in the more provincial regions of Britain. In Manchester, the rapid expansion of the newspaper press paralleled Manchester’s rise to become the first industrialized city. The majority of the newspapers contained in Section IV were published in Manchester during the period c.1750-1820. Many scholars argue that this period precluded the real industrial age that began in earnest from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Others argue that this period was crucial in its own right because it laid the foundations and prepared the way for the height of the industrial revolution that was to come. Either way, Manchester underwent massive changes during this time, and the newspapers of the day provide a fascinating insight into how this change affected all aspects of society.

The market for cotton rapidly expanded during the eighteenth century and Manchester was well-placed to take full advantage of this. Indeed, many factors combined to make Manchester one of the world’s central marketplaces for the sale and manufacture of cotton products. Manchester was at the centre of a growing network of roads, canals, and navigable waterways which transported raw cotton and coal to and from other towns and ports like Liverpool. In conjunction with this, a long history of investment in warehouses led to burgeoning districts that provided commercial premises, such as Oswald Mosley’s Cotton Exchange built in 1729, from which to store, display and trade goods. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the production of cotton benefited from technological innovations in engineering and machine making and, as a result, it became increasingly mechanized and factory based. This all led to a dramatic increase in urban and economic growth: population figures grew as Manchester’s wealth creation potential attracted both workers and merchants and the commerce and finance sector became as important to Manchester’s economic status as the manufacturing industries. By the end of the eighteenth century Manchester had become a town of national significance.

Despite all of this growth and success, Manchester, like many other growing industrial towns, had no representation in Parliament during the eighteenth century. As a result of this, newspapers played an important role in representing and shaping public opinion and they increasingly had the power to influence political and public matters. Newspapers were the only reputable source of information about parliamentary proceedings, news and debates until parliamentary official records (Hansard) became available. With the rise in number of provincial newspapers, people were more informed about parliamentary matters than ever before, even though many were unable to vote. Thus the newspapers became a major force behind the political reform movement that took place in Manchester between 1715 and 1830, which saw increasing numbers of disenfranchised people trying to influence parliament via petitions.

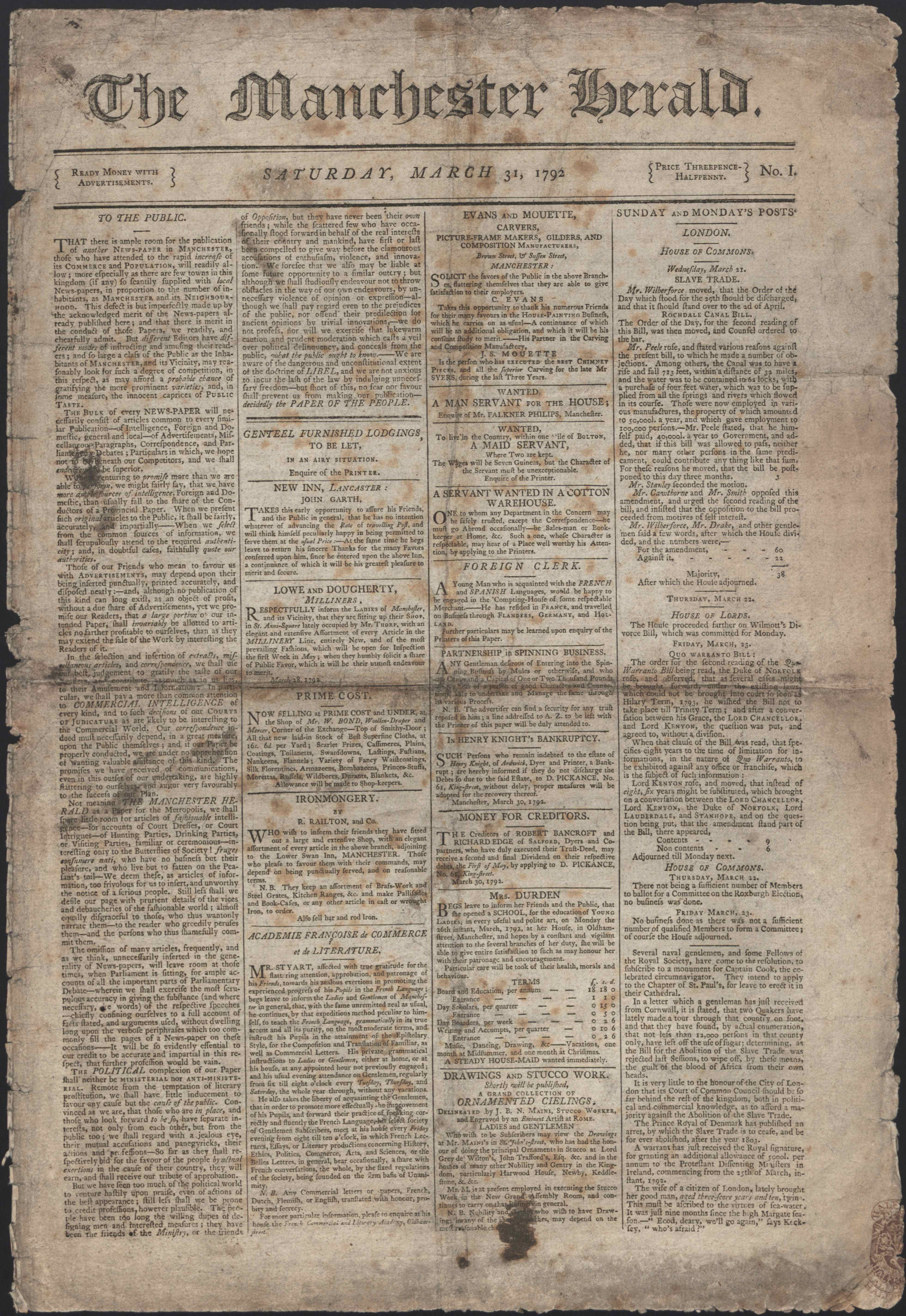

In the late eighteenth century an anti-slavery movement led by the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade swept Britain. In 1788, a mass-petitioning campaign was initiated in Manchester in an attempt to end the slave trade. Hundreds of towns followed Manchester’s lead and it became the largest nationwide mobilisation of campaigners ever organized. That same year the first legislation was passed to regulate the slave trade. Another campaign was then undertaken in 1792 with a record number of petitions being presented to the House of Commons. An article in the Manchester Herald on the abolition of the slave trade from 1792 conveys, using strong rhetoric, the campaign’s hopes for victory:

Though the triumph of reason and humanity has been deferred, we have reason to think it will not longer be delayed. A cause which concerns all mankind, by resting on the principles of universal benevolence, and which daily requires strength and numbers, cannot fail of obtaining a speedy victory, over the unfeeling avarice which wishes to conceal, and the timid ignorance which dreads to unfold the true interests of humanity. (Manchester Herald, Issue 1)

The article also contains details of the efforts made to raise financial support for the campaign and to disseminate ‘knowledge’ about the cause. The claim in this article that petitions flowed ‘in from all parts of Great Britain’ is confirmed in a later issue of the Manchester Herald (Issue 2) which contains a long list of all of the places that submitted petitions to the House of Commons. This issue of the Manchester Herald also features a lengthy account of William Wilberforce's speech to the House of Commons in support of the abolition of the slave trade.

In many ways it is not surprising that the Manchester Herald was in support of parliamentary reform. The two men who edited the newspaper, Thomas Walker, a cotton merchant, and Thomas Cooper, a barrister, formed the Manchester Constitutional Society in 1790 which was aimed at the burgeoning non-conformist middle classes. Spurred on by the French Revolution and influenced by the ideals contained in the popular book Rights of Man by Thomas Paine, the Society succeeded in persuading local newspapers such as the Manchester Mercury and the Manchester Chronicle to publish their articles on parliamentary reform. But, by 1791, the local press became increasingly reluctant to give Walker and Cooper a voice and so they decided to edit their own newspaper. The first edition of the Manchester Herald was published on the 31st of March 1792. In the first issue, the Editors wrote an introductory piece 'To the Public' that explains what kind of news and content the Herald will, or, as the case may be, not, contain:

…we shall spare little room for articles of fashionable intelligence – for accounts of Court Dresses, or Court Intrigues – of Hunting Parties, Drinking Parties, or Visiting Parties, familiar or ceremonious – interesting only to the Butterflies of Society!...Still less shall we defile our page with prurient details of the vices and debaucheries of the fashionable world…(Manchester Herald, Issue 1)

The piece ends by declaring that ‘no fear nor favour shall prevent us from making our publication - decidedly the PAPER OF THE PEOPLE.’ Manchester’s Tory loyalists responded in December 1792 by instigating riots against the Herald’s offices and the radicals’ homes. Walker and others were tried for sedition and the Herald was prosecuted to such an extent that it soon after ceased publication. After this Tory retaliation, political radicalism remained subdued until the Peterloo riot and massacre in August 1819. For a report of this well-known uprising see an account in the Observer from the same year.

Although many middle class radicals moderated their politics after the demise of the Manchester Herald, another newspaper emerged to cater to the non-Tory market. William Cowdroy founded the Manchester Gazette in 1795. Cowdroy put forward his proposal for a new newspaper to the public in a broadside which was published in 1795 with the title Pr[oposed?] new Manc[hester weekly?] W. Co[wdroy] for eleven year[s publisher of] the Chester [chroni]cle…having been for some time engaged in preparing for publication, a weekly paper under the title of The Manchester Gazette or Weekly Advertiser…

While it was considered by many to be of poor quality, the Manchester Gazette survived because it of its political line: it was the only newspaper that was popular with radicals due to its anti-war and anti-tax stance. When William Cowdroy died in 1814 his son became the new editor. Worried by the paper’s low sales he tried to improve its quality by encouraging members of a moderate, middle class, political reform group (that Cowdroy was also a member of) to contribute to articles. Members of the group included John Edward Taylor, Archibald Prentice and John Shuttleworth. They regularly met at John Potter’s house who was a well-known Liberal in Manchester. They strongly objected to industrial cities, like Manchester, being denied representation in the House of Commons. They were also opposed to the Corn Laws that had been passed in 1815. The men held nonconformist religious views and thus advocated religious toleration and they also supported Free Trade. Many of their views and opinions are contained in articles they wrote for the Manchester Gazette. Cowdroy’s strategy seems to have worked because by 1819 the Manchester Gazette was selling over a 1,000 copies a week.

In many ways, then, newspapers thrived on the back of industrial progress and were very closely linked to the political reform movement that was gaining momentum in Britain. But the far-reaching effects of newspapers did not end there. Newspapers were also integral to the rise of advertising in the eighteenth century. As the circulation and readership of regional newspapers widened, businesses became more aware of the potential for advertising and selling their products via printed advertisements on a nation-wide scale. A cycle emerged that sustained the growth the growth of advertising: advertisements provided newspapers with a vital source of income and profit, enabling newspapers to charge less for the paper which, in turn, mesnt that more people would read it. This large readership attracted more advertisers and so the cycle continued. By the end of the eighteenth century, advertisements made up a large part of the content of newspapers. Fittingly enough, the word ‘advertiser’ began to appear in the title of many papers. The newspaper Harrop's Manchester Mercury, for example, changed its title to Harrop's Manchester Mercury, and General Advertiser after just eight issues. Before the nineteenth century, the majority of advertisements were for books and medical products. The burgeoning medical market was particularly reliant on successful marketing and branding. Indeed, the sellers of successful products like ‘the famous Cordial’ Daffy’s Elixir, which is advertised in Harrop’s Manchester Mercury (1752-53), used a range of techniques to attract customers and to differentiate themselves from similar ‘quack’ medicines or counterfeit copies. It was fairly rare for advertisements to contain images but this advertisement contains a small, eye-catching logo that serves to emphasise the product’s authentic brand.

The advertisement warns potential buyers not to ‘miss the Shop as Whitworth’s pretend they sell the same Sort of Daffy’s as that been Sold in the Family for above thirty Years, tho’ they have not had any from the same MAKER since October 1751’. Much of the advertisement is devoted to listing all of the ailments that the Elixir is claimed to have cured:

…this purgative Spirit-reviving Cordial, is peculiarly adapted to answer the Ends of an universal Family Medicine. Multitudes of incredible Cures done by it might be produc’d...Surfeits got by hard Drinking, Dropsy, Convulsions, Asthmas, Cholick and Griping of the Guts, Scurvey Root and Branch Consumptions and bad Digestions, and in many other Distempers it has give Relief, and did Numbers of Cures in Great Sickness in 1725 and 1726. (Harrop’s Manchester Mercury 1752-53, Issue 1)

As the eighteenth century gave way to the nineteenth century, newspaper advertising continued to thrive in spite of the various stamp taxes that were imposed and newspapers continued to play an integral role in the development of a consumer culture and society.

Post-1850 other cities and industries gradually caught up with Manchester and its comparative economic and industrial importance declined. Newspapers, on the other hand, were firmly established in Manchester and many other provincial areas and their numbers and influence continued to rise throughout the nineteenth century.

List of Module IV Journals by Subject Area (links to first available volume)

British Volunteer, and Manchester Weekly Express

Cowdroy's Manchester Gazette

Harrop's Manchester Mercury

Manchester Chronicle: or Anderton's Universal Advertiser

Manchester Herald

Manchester Journal

Manchester Telegraph

Patriot

Prescott's Manchester Journal

Pr[oposed?] new Manc[hester weekly?] W. Co[wdroy]

Supplement to The Lancaster Gazette

Wheeler's Manchester Chronicle

London

Bee [The Bee Reviv’d]

Bell's Weekly messenger

British Critic

Chester Chronicle

Lady's Magazine

Letter to Every Person in Great Britain

Memoirs of Literature

New Memoirs of Literature

New Review

Observer

Phoenix Britannicus

Present State of Europe

Reports of the Humane Society

Whitehall, July 16. 1695

European Journals

Histoire de la République des Lettres et Arts en France

Spectacles de Paris

News, Politics and Current affairs

Bee [The Bee Reviv’d]

Bell's Weekly Messenger

British Volunteer, and Manchester Weekly Express

Chester Chronicle

Cowdroy's Manchester Gazette

Harrop's Manchester Mercury

Letter to Every Person in Great Britain

Manchester Chronicle: or Anderton's Universal advertiser

Manchester Herald

Manchester Journal

Manchester Telegraph

Observer

Patriot

Prescott's Manchester Journal

Present State of Europe

Pr[oposed?] new Manc[hester Weekly?] W. Co[wdroy]

Supplement to The Lancaster Gazette

Whitehall, July 16. 1695

Literature, Theatre and Arts

British Critic

Memoirs of Literature

New Memoirs of Literature

New Review

Spectacles de Paris

Magazines and Miscellanies

Bee [The Bee Reviv’d]

Lady's Magazine

Phoenix Britannicus

Reports of the Humane Society

Back to the Top

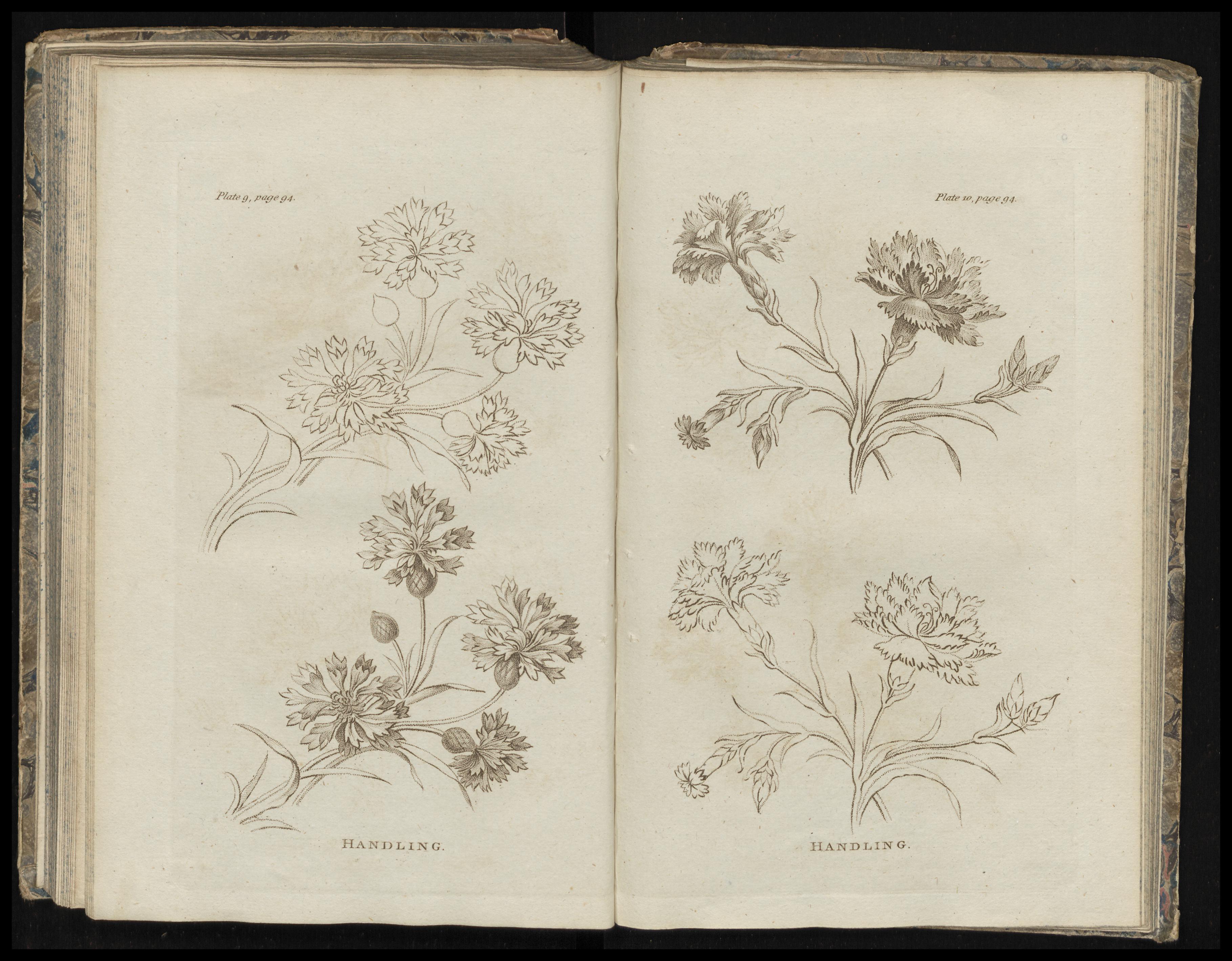

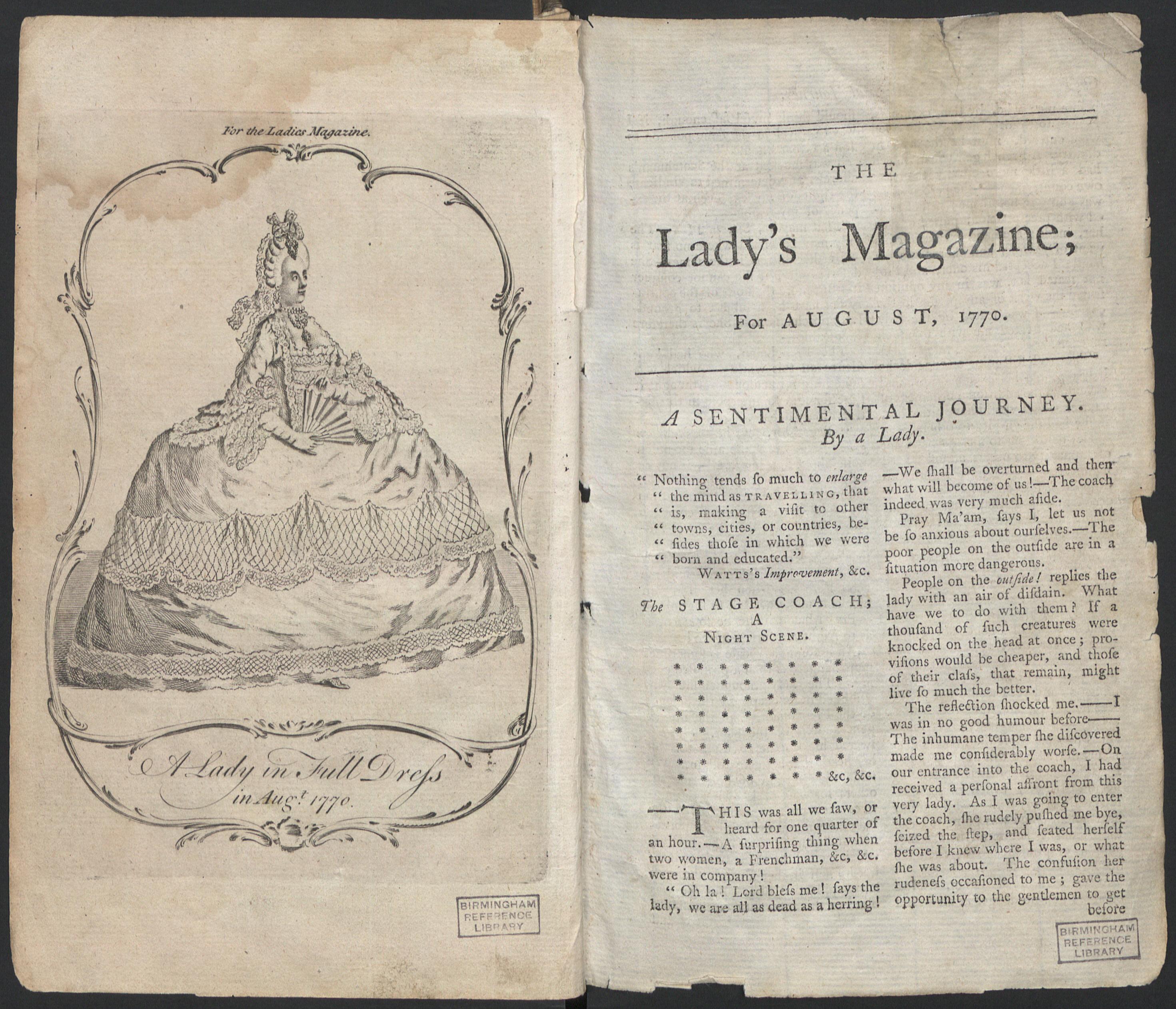

In Eighteenth Century Journals V, we include the full run of The Lady’s Magazine: or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex, a periodical which ran for sixty-two years from 1770 to 1832, before merging with its rival The Ladies Museum in 1832. The Ladies Museum was launched in 1798 as The Lady’s Monthly Museum, the first two volumes of which are also included in this section.

In Eighteenth Century Journals V, we include the full run of The Lady’s Magazine: or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex, a periodical which ran for sixty-two years from 1770 to 1832, before merging with its rival The Ladies Museum in 1832. The Ladies Museum was launched in 1798 as The Lady’s Monthly Museum, the first two volumes of which are also included in this section.

The Lady’s Magazine was issued monthly and is significant for its longevity in a market - the periodical press - where publications were largely short-lived. Its longevity and ability to survive and endure beyond a number of its rivals in a competitive market is not its only remarkable feature. In the intellectual climate of the coffee house and the largely male dominated literary society it produced, and in the face of a print culture, which, for the most part, delivered newspapers, periodicals and journals for a male readership, The Lady’s Magazine is a forerunner of the emergence of not only a targeted female readership but also provides a platform for women, as both contributors and consumers, to engage in the literary discourse of the eighteenth century.

The Lady’s Magazine, as suggested by its title, marketed itself directly to a middle-class female readership. The magazine’s primary objective was to provide a regular periodical that contained material designed for the entertainment and improvement of women in a manner accessible to the "house-wife as well as the peeress" (The Lady’s Magazine, August 1770). It covered a wide range of topics and genres: fashions, poetry, remarks on society, biographies of prominent men and women, culture, travel writing, moralising essays, short stories, serials, translations, advice, recipes, medicinal receipts, theatrical and literary reviews, domestic and foreign news, births, deaths and marriages. The textual content was often complemented with elegant engravings, music sheets, embroidery patterns, and later, colour fashion plates.

The translator of Rousseau’s Emilia will excuse us for repeating the complaints of a numerous groupe of correspondents, on account of the intermission of her translation; and as we cannot much longer bear the clamours of our friends on that account, she will excuse us if we snatch the inactive pen out of her ink-stand, and employ it in completing what she is in honour bound to complete.

The words “honour” and “obligation” were often used against writers who ceased their contributions, leaving serials unfinished and editors and readers alike, frustrated.

Over the course of its sixty-two year run, readers of the magazine today can trace shifts in public opinion, taste, culture and political climate, making the Lady’s Magazine an insightful and enlightening source for the study of eighteenth and early nineteenth century social and cultural history. The magazine also provides research opportunities for students and scholars interested in eighteenth century print for women and the role that women played, as contributors and consumers, in the literary marketplace.

Over the course of its sixty-two year run, readers of the magazine today can trace shifts in public opinion, taste, culture and political climate, making the Lady’s Magazine an insightful and enlightening source for the study of eighteenth and early nineteenth century social and cultural history. The magazine also provides research opportunities for students and scholars interested in eighteenth century print for women and the role that women played, as contributors and consumers, in the literary marketplace.

The Selection of Material for Eighteenth Century Journals

The purpose of Eighteenth Century Journals is to make available digitally for the first time unique or extremely rare eighteenth century periodicals. The primary aim is to promote a truly broad representation of the culture of print journalism in the eighteenth century. Therefore, there was no selection of titles on the basis of subject matter or theme; or by how well-known a title was, either by contemporary readers or scholars of today. Instead, the periodicals included in this project have been carefully chosen to convey the eclectic nature and evolution of the publishing world between 1685 and 1835.

Module I provides digital versions of content originally in Adam Matthew Publication’s microfilm project Eighteenth Century Journals, from the Hope Collection at the Bodleian Library, Oxford. We have enriched the original content with a further nineteen titles requested by scholars, also taken from the Hope Collection.

Module II continues the series and is based on the holdings of the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas, Austin, which contains one of the finest collections of rare 17th and 18th century British periodicals in the world. The starting point for selection was British Newspapers and Periodicals 1632-1800, a descriptive catalogue of the early periodical holdings at the University of Texas, compiled by Powell Stewart in 1950. The selection process was then widened to include additional titles accessioned after Powell Stewart’s original inventory, and items from the Queen Anne list of serials at the Center.

In response to the encouragement of scholars and librarians, Module III focuses on journals published outside of London. A group of titles were selected from Canada, the Caribbean and India from British Library Newspapers at Colindale. Further journals were then added from Cambridge University Library which has a large number of rare titles published in many cities and towns around Ireland. A number of important journals produced in Edinburgh, Canterbury and Cambridge were also included from the Cambridge holdings.

This commitment to publishing unique and rare newspapers and periodicals from outside of London continues with Module IV. Key material was selected from Chetham’s Library in Manchester and focuses predominantly on Manchester as an emerging city during a time of momentous change and growth. To supplement this, selected periodicals, including some European journals, were sourced from the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds.

In Module V we have included the full run of The Lady’s Magazine (1770-1832) in response to encouragement from scholars. As no single library holds a complete set, we have pieced together the entire run from three libraries, the British Library, Birmingham Central Library and Cambridge University Library, and one private collection. The Lady’s Magazine is an insightful and enlightening source for the study of eighteenth and early nineteenth century social and cultural history and a major source for scholars of gender, social and literary studies. To complement the Lady’s Magazine, we have also included a selection of periodicals that are social, cultural and literary in scope from Cambridge University Library and Liverpool John Moores University Library.

All of the titles in this portal have been carefully screened against other eighteenth century academic resources to ensure that there is minimal overlap. Resources checked include: Primary Source Media’s microfilm collection Early English Newspapers; Chadwyck-Healey’s Early English Books Online (EEBO); Gale’s 19th Century British Library Newspapers, Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO) and The Burney Collection; and Proquest’s British Periodicals.